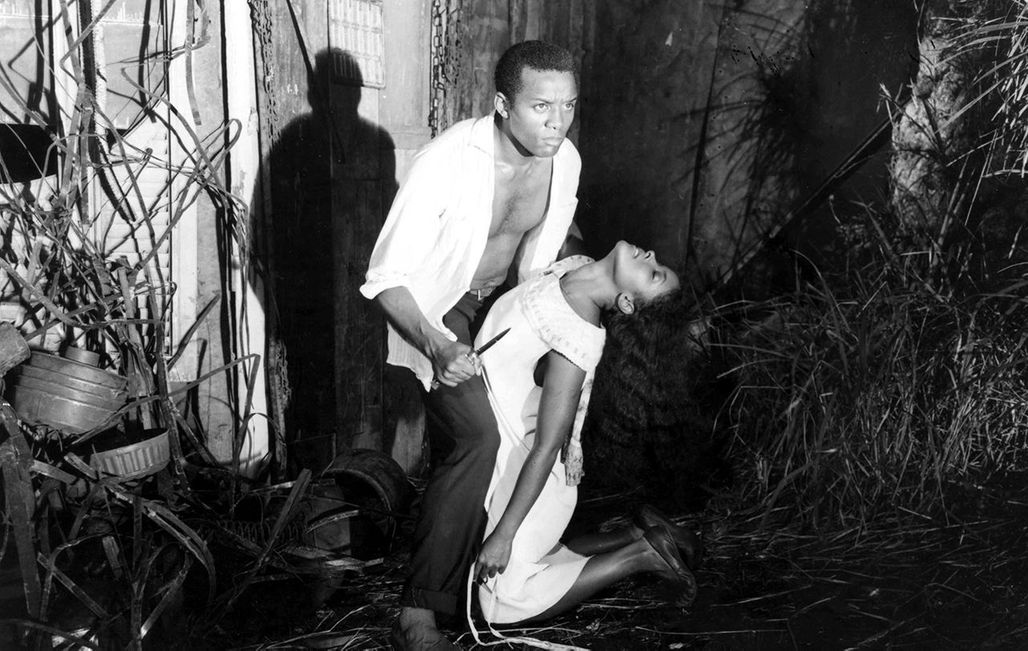

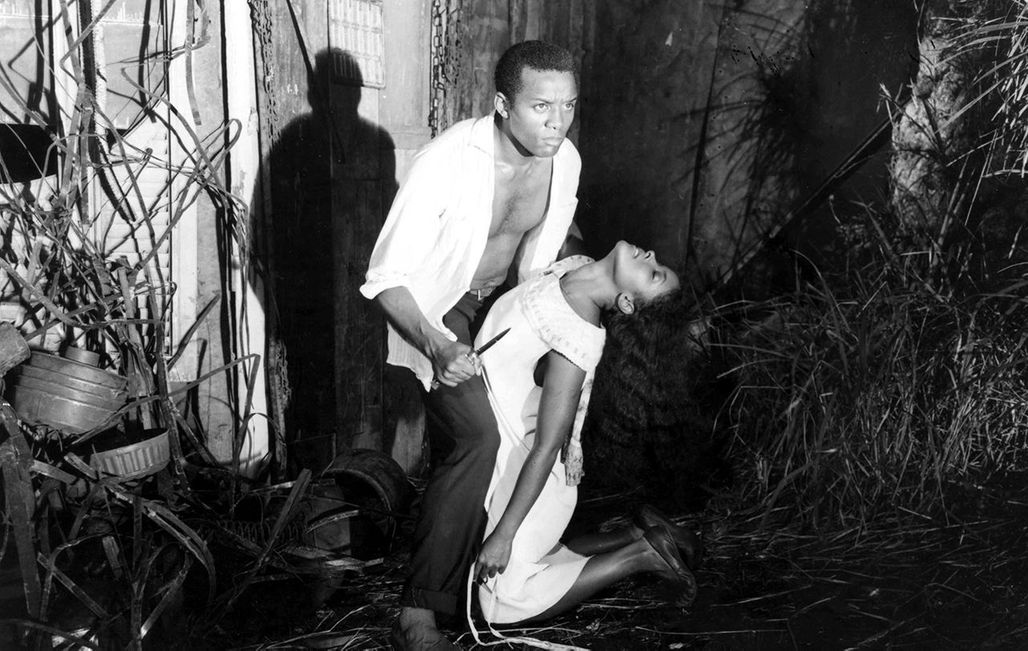

Interview with Amir Labaki about Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro), the 1959 Palme d’or

Journalist for Valor Econômico and author of 13 books on cinema, Brazil’s Amir Labaki shares his vision of Marcel Camus' Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro), a magnificent 1959 Palme d'Or that has been re-released this year at Cannes Classics in a restored version. When it was released, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, transposed to Rio de Janeiro by the French director, was as acclaimed by the public as it was devalued by the critics.

The public adored it but the critics, including Jean-Luc Godard, were scathing of the film when it won the Palme d'Or. How do you explain this?

Black Orpheus mixes two popular formulae of the time: the classic structure of melodrama and the exotic appeal of the Tropics. Marcel Camus distances himself from Vinicius de Moraes' play by adapting it to a Rio de Janeiro full of clichés: those postcard scenes, with the beaches and the Corcovado, the poor, sensual and colourful favelas, the Carnival as an glimpse of a possible social integration, the rituals of the macumbas as a kind of "Carioca voodoo"… All this was wrapped in a musical genre that was beginning to conquer world: Bossa Nova, represented in the film by the composers Antônio Carlos Jobim (1927-1994) and Luis Bonfá (1922-2001).

Black Orpheus was a huge commercial success worldwide, but critics resisted. The Brazilians predictably rejected Camus' exoticism and unrealistic approach, as our national cinema preferred the pioneering realism of earlier films such as Rio, 40 Degrees (1955) and Rio, Zona Norte (1957), by Nelson Pereira dos Santos (1928-2018), precursor of pre-Cinema Novo. The French and international critics who rejected the film perceived Black Orpheus as ultra-theatrical, in contrast to the New Wave, which was already beginning to make its mark on the film scene.

Where does the magic of Black Orpheus lie?

Despite all that is described above, there is no denying that this tragic love triangle set in a tropical setting and carried by characters in vibrant and colourful costumes, exudes a romantic and almost universal phantasmagorical feeling. Camus transposes the Greek myth of Vinicius de Moraes' play to a contemporary Rio de Janeiro, and creates his own 'Carioca myth' by revisiting the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The colours of Rio are different, the carnival has a different dynamic, even the characters have a different vocabulary and a different Carioca accent, but the French director sacrifices realism on the altar of own Dionysian utopia. The magic of Black Orpheus is there, Camus' very personal "betrayal" has given rise to a film with resonances as perennial as they are popular.