Robot Dreams: an interview with the director Pablo Berger

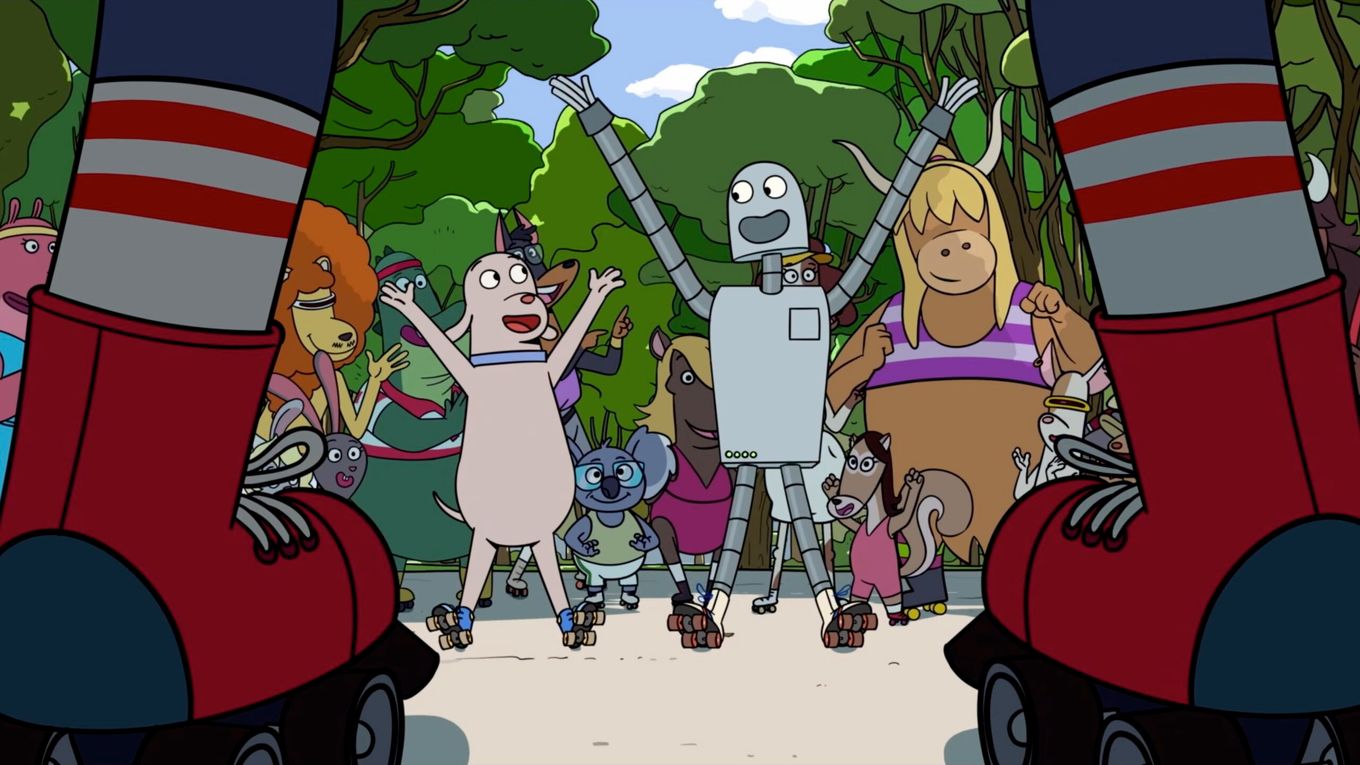

Each Pablo Berger is an exercise in style. After Blancanieves and Abracadabra, the Spanish director is trying his hand at animation with Robot Dreams, a Special Screening. Adapted from a New York graphic novel, the film focuses on the friendship between a dog and a companion robot, with tenderness and melancholy.

What made you want to adapt this graphic novel?

I had never imagined making an animated movie but the story of the book left an impression on me. It made me laugh and dream. It surprised me and made me reflect on friendship and its fragility, on how to overcome the end of a relationship. The soul of this story pushed me to make Robot Dreams.

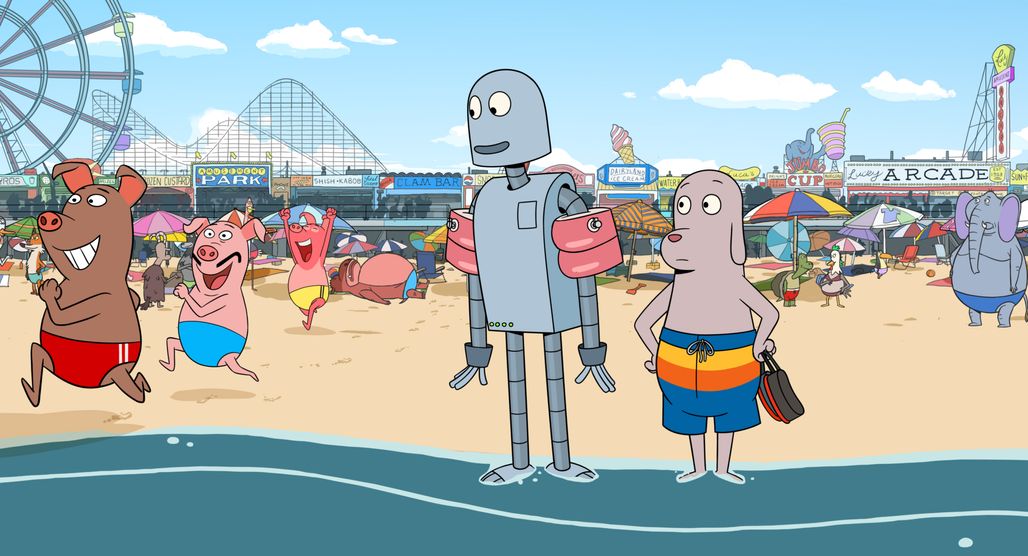

Is New York a city that you know and that inspired you?

I lived in New York for ten years in the 90s, but the film takes place a little before, in the 80s. I wanted to depict a city from another time, which doesn’t exist anymore, before globalization does away with the particularities of every city. When I was living there, New York was unique. Without a doubt the capital of the world culturally and economically, the place where you had to be. My team worked a lot on this project, we looked for images, photos and films to portray the New York of the time as faithfully as possible, as we would have done for a period piece. We didn’t want New Yorkers to see their city from the point of view of someone Spanish or French or Japanese. It was a challenge.

None of your films are alike. How did you take up the exercise of animation?

What attracted me was the risk. Curiously, in all my films, I’ve made use of a storyboard, something fundamental in the preparation of an animated film. I’m a very patient director, I work attentively, which is essential for this exercise. It’s as if all my previous films had prepared me to make this one. It’s not a journey into the complete unknown because animation is not a genre but rather another way of working.

Like Blancanieves, Robot Dreams has no dialogue. Was this just as delicate an exercise?

It was harder because in Blancanieves, there were intertitles that provided information. In Robot Dreams, there is direct sound. The characters laugh, shout, breath, we hear doors close… But there’s no text here. It was a challenge but ultimately, in my previous films, there wasn’t much dialogue. The images spoke. Tackling writing through images is what I prefer in the creative process and that was essential for this film.

It’s a friendship film for children… and for adults?

My films are there for everybody. Everybody should be able to approach it at their level. For kids, it’ll be a story of love or friendship. An adult will interpret it as a film about couples or maybe about the loss of someone dear. It’s very open. The fact of not using dialogue allows the spectator to make the film their own depending on their own experience.